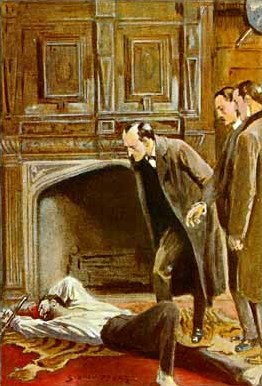

It’s a staple of the detective genre that the heroic investigator picks up on some tiny clue, some inconsistency that unravels an otherwise perfect crime. They spot that only one dinner guest could have passed through the kitchen in the two-minute window to poison the bride’s champagne glass, or that the mystery turns on whose muddy boots were in the porch as only the owner of those boots could have followed the groundskeeper to learn where the key of the gun cabinet is stored. The key little clue is small, easily overlooked, and seemingly unimportant – unless you’re a great detective.

It’s a staple of the detective genre that the heroic investigator picks up on some tiny clue, some inconsistency that unravels an otherwise perfect crime. They spot that only one dinner guest could have passed through the kitchen in the two-minute window to poison the bride’s champagne glass, or that the mystery turns on whose muddy boots were in the porch as only the owner of those boots could have followed the groundskeeper to learn where the key of the gun cabinet is stored. The key little clue is small, easily overlooked, and seemingly unimportant – unless you’re a great detective.

The unpredictable, improvisational nature of roleplaying games makes it tricky to deal with such granular information. In other media, the author can ensure that the key clue is mentioned in passing; the reader can page back in the novel or rewind the movie and check to see if the author played fair. The challenge there is to present the information obliquely, letting the audience see it but not notice it.

A roleplaying game faces some very different challenges. Firstly, here, audience and detective as one and the same. Just because the reader fails to notice the key clue doesn’t mean the fictional detective also missed it; the narrative continues regardless of the audience’s degree of awareness.

Secondly, while the author can be sure the detective spots that key clue, it’s harder to ensure that in a roleplaying game without putting undue weight on it. If you go out of your way to point out that, say, Reverend Green is hanging around by the gun cabinet, the players will correctly assume it’s of great significance. If you try to conceal the importance of Reverend Green by mentioning that he’s lurking by the gun cabinet, but Ms. Scarlet’s playing with a sharpened letter-opener while Professor Plum’s talking enthusiastically about his new habit of lead pipe collecting, then you hide the key clue but run the risk of the players not remembering it and stalling the investigation.

Some techniques to honour this whodunnit tradition in GUMSHOE:

The Reference Chart: You can subtly draw the players’ attention to a particular aspect of the mystery by providing them with a handout. If the layout of the mansion’s really important, give them a map of the mansion. If it’s all about the relationships of the suspects, then maybe a family tree or a list of family members. If the mystery hinges on timing, then give them a timeline with the established events already listed, so they can literally fill in the gaps. Bonus points if you make the chart diegetic (“here’s the seating chart from the wedding”)

Giving the players a chart tells them that this part of the mystery is important and that they should pay attention, without making the key clue stick out like a sore thumb.

The Two-Part Clue: The whole point of a key little clue in detective fiction is that it’s overlooked when first encountered, and it’s only in retrospect that the detective realises its significance. The GUMSHOE rules promise that the investigators will never miss a clue if they use the right ability at the right moment – but it’s really unsatisfying to take the moment of deduction away from the players. If the mystery hinges on, say, the view from the attic window, then it’s dull to just say “ok, who has Architecture? Yeah, you can tell that the tennis court is visible from the attic, so Bob could have seen his wife canoodling with the tennis instructor before he was murdered.”

The trick is to making the discovery of the key little clue into some active decision by the players. Have a regular clue that calls attention to the key little clue, and then have the players deploy their investigative abilities and/or deductive talents to uncover it. For example, maybe Notice finds a discarded cigarette near the attic window, suggesting someone was looking through it – and the players have already heard gossip suggesting an affair between the wife and the tennis coach. Or maybe the Chemistry identifies the poison residue in the bride’s champagne glass, and then it’s up to one of the players to ask “oh, can I use Oral History to question all the guests and work out if any of them had access to the glass just before the wedding toast?”

The Extra Murder: Another common trope in murder mysteries is the second murder, where the killer strikes again (often, either as part of a cover-up, or because the second killing is linked to the motive of the first, like eliminating the other potential inheritors to an estate). In a roleplaying game, you can use the second murder to draw the investigators’ attention to the key little clue – maybe Bob pushes his second victim out of that fateful attic window, or questioning other guests at the wedding about the second victim reveals that Aunt Gertrude was sitting right next to the kitchen door and kept complaining whenever the waitstaff went in and out… and how she got really peeved when one of the guests went into the kitchen to complain about the hollandaise sauce.