Fall of Delta Green, News

Call of Chicago: Sous les Pavés, Carcosa!

“They have no time to think of surrender. Are they heroes — these Parisians?”

— Robert W. Chambers, “The Street of the First Shell” (1895)

Right about now, just about fifty years ago as I write this, France had no functioning government. I mean, more than usual. Charles de Gaulle, President of France for the last decade, had vanished from the Elysée Palace in the midst of strikes and protests that paralyzed – or vitalized – Paris and left France on the brink of revolution. Half a million protesters marched through the streets of the capital in the dawn light of May 30, 1968, chanting “Adieu, de Gaulle!”

The “May 68,” as it has come to be known, began with a student strike in March at the miserable conditions at the University of Nanterre outside Paris. Some of the Nanterre activists (calling themselves enragés after the grubbiest left-radicals of 1793) fled to the Sorbonne in Paris; when the police closed Nanterre and entered the Sorbonne to recapture the rabble-rousers, 20,000 Sorbonne students rose in protest on May 6, 1968. Police brutality against the students in turn brought the unions and the Communists into the streets, hoping to tap into the energies of the enragés for their own causes.

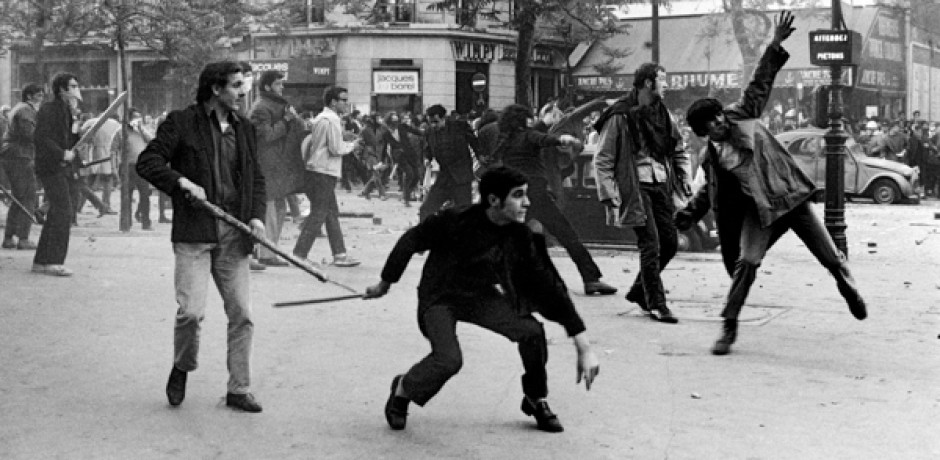

A million people marched in Paris on May 13, setting off a series of general strikes and workers’ seizures of factories all over France. The students retook the Sorbonne and declared it a “people’s university.” Barricades went up, and paving stones flew at cops’ heads. By May 22, two-thirds of French workers were on strike. On May 27, the UNEF, the national student union of France, held a meeting at the Sebastien Charety stadium in Paris; the 50,000 attendees demanded the end of the French state, and the Socialists hurried to pledge their support the next day. On May 29, de Gaulle got into a helicopter and flew away.

We Have a Situation Here

“Where the real world changes into simple images, the simple images become real beings and effective motivations of hypnotic behavior.”

— Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (1967)

A plurality, and perhaps a majority, of the Occupation Committee of the Sorbonne were members of, or otherwise identified themselves with, the Situationist International. The SI believed in radical non-hierarchy – possibly because of SI founder Guy Debord’s distrust of the Stalinist tendency throughout the contemporary Left – but Debord provided the main theoretical juice for what the Situationists claimed they never called “Situationism.”

In a nutshell, Situationism expands Marxist theory of alienation from the workers to all of society. Ever since World War One, Debord wrote, “the Spectacle” of consumption and commodified objects by its very nature has dominated and controlled every act, thought, and word not just of the proletariat but of everyone who buys or watches. These illusory bread and circuses recreate the oppressive class order within themselves, and “recuperate” even seemingly rebellious acts as a necessary dramatic element within the Spectacle. Examining politics, culture, and capitalism as art produces awareness of the Spectacle but cannot escape it; psychogeography can map the effects of geography and the city on emotion and mind but cannot obviate them.

Only by random artistic inspiration and acts of parodic reinterpretation called “detournement” can the willful Situationists win “the game of events,” free themselves from the Spectacle, and call their own vision of true democratic equality into being. From 1957, when the SI emerged out of a radical surrealist movement, they (or at least Debord) grew ever more directly political.

Politically, to the extent they mapped onto the normal spectrum, the Situationists could be called left-anarchists. Debord mocked anarchists as “mystics of nonorganization,” a tag which could as easily apply to the SI. Their snark and individualism appealed to student radicals such as those in Nanterre and the Sorbonne. Those students dug up precursors to their new movement, from the dynamiter Ravachol to the Marquis du Sade to a certain anonymous playwright.

A Situationist cell in the Sorbonne reads a banned play, and acts. How better to rip the mask off the Spectacle, to separate the lying signs of capitalism from the true signifieds of feeling, than by weaponizing words that undermined so-called reality? They set the Pallid Mask against the mask of the Spectacle, attacking police from the new boulevards of the “Bablyon-Carcosa” they had seen emerging through the tear gas as the Seine billows outward into a great black Lake.

Operation CHARENTON

“Coming soon to this location: charming ruins.”

— Situationist Graffito, Paris 1968

Amidst the Situationist graffiti that rapidly covered the walls of Paris’ Left Bank, a program stringer notices a Sign painted in yellow, a Sign that Admiral Payton has made sure to brief his Paris operatives on since he saw it in 1955. Every DELTA GREEN asset in France gets the alert signal: A day at Longchamp. But how to find the center of an invasion inside a revolution? Payton suggests a random walk: seeking the Sign calls the Sign to you.

Payton learned from Operation BRISTOL that guns and confrontation only feed Hastur. So what to do about it? Detourn the Sign, spray-paint petals sprouting from it, create a yellow fleur-de-lis that angry leftists will be sure to obliterate beneath scarlet hammers, sickles, and stars. If you find copies of the play, destroy it, yes; if you see a street performance under black stars, disrupt it, absolutely. But until then, lean into the Spectacle; make it work for you. Behave like a character in a spy film, turn cosmic convulsion into cheap stereotype. Reinforce plastic reality, tread Carcosa as a stage set, recuperate the King in Yellow as nothing more than a revolutionary poster, and then rip him up.

Agents fan out into Paris, losing touch with each other in a city writhing between two masks. Your Agents doubtless play the crucial role, although other teams in other Iles du Paris report their own strange victories. A Gaullist rally 800,000 strong marches through Paris on the afternoon of the 30th. De Gaulle returns from Germany with the army’s support, orders the workers back with raises, orders the colleges reopened under proper prefects, orders the Spectacle restored. The Communists and Socialists go along, and he crushes them in the elections the next month. Only the normal despair and alienation breathes Parisian air again.

Or was the explanation different? Was Payton’s aim wrong, even if his ammunition was sound? Had the Situationists, alert to every nuance of falsity and screen memory, uncovered the truth about the world? Were they trying to awaken the world from its unnatural prison? After all, Debord’s description of the Spectacle sounds very familiar, to my ears:

To the extent that necessity is socially dreamed, the dream becomes necessary. The Spectacle is the nightmare of imprisoned modern society which ultimately expresses nothing more than its desire to sleep. The Spectacle is the guardian of sleep.

Iä! Iä! Spectacle fhtagn!