News, Trail of Cthulhu

Call of Chicago: The Dream-Quest of Gertrude Abercrombie

“Surrealism is meant for me, because I am a pretty realistic person but don’t like all I see. So I dream that it is changed. Then I change it to the way I want it. It is almost always pretty real. Only mystery and fantasy have been added. All foolishness has been taken out. It becomes my own dream.”

— Gertrude Abercrombie

Gertrude Abercrombie met Gertrude Stein in 1935 when her friend Thornton Wilder invited the novelist to lecture at the University of Chicago, and dubbed herself “the other Gertrude” in response. Almost entirely self-trained as a painter (barring two courses at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago), her spare, almost barren works form the other pole of Chicago surrealism, against Ivan Albright’s more famous extravaganzas of rococo decay.

Born in 1909 to traveling opera singers, Gertrude always had music around her, and learned to play piano from a young age. Her mother moved the family to Berlin to study in 1913, but the outbreak of war drove them back home to Illinois and eventually to Hyde Park, the academic bohemia on the South Side of Chicago, in 1916. Once she got work as a commercial artist in the 1930s, and then with the WPA, she moved into a large apartment in Hyde Park and immediately accumulated a circle of artistic friends and lodgers: not just painters and sculptors but anthropology student (and future danseuse) Katherine Dunham, future novelists James Purdy, Saul Bellow, and Wendell Wilcox, and architect Harold Noecker.

Her first show (and sale) came at the Grant Park Outdoor Fair in 1933, and she rapidly climbed the ranks of Chicago’s native artists: a group show at Kroch’s bookstore later in 1933, a solo show at the Art Institute in 1944, and her first New York City show at the Associated American Artists Gallery in 1946. By this time, she was painting prolifically (over 100 pieces in 1952 alone) and had married the music critic Frank Sandiford, her second husband, who introduced her to the jazz greats inventing bebop: Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, and Sarah Vaughan. Gillespie’s Modern Jazz Quartet lived in her three-story Hyde Park graystone from 1952 to 1954, and the house rocked to jam sessions after weekend gigs, Gertrude on the piano.

Her 1940s and 1950s salons included not just jazzmen but a new pack of surrealist artists: John Wilde, Jerome Karidis, and Dudley Huppler, who all came down from Wisconsin on the weekends. Chicago, like New York and Europe, was turning away from surrealism and toward abstraction. Gertrude became less cool, less the center of everything. Her last solo show in Chicago coincided with the breakup of her marriage in 1964; by then her alcoholism had intensified her pancreatitis and arthritis, eventually confining her to a wheelchair or one room of her house. She died during a retrospective of her career at the Hyde Park Art Center in 1977.

Dreamhounds of Chicago

“‘This is Thalarion, the City of a Thousand Wonders, wherein reside all those mysteries that man has striven in vain to fathom.’ And I looked again, at closer range, and saw that the city was greater than any city I had known or dreamed of before. Into the sky the spires of its temples reached, so that no man might behold their peaks …”

— “The White Ship,” H.P. Lovecraft

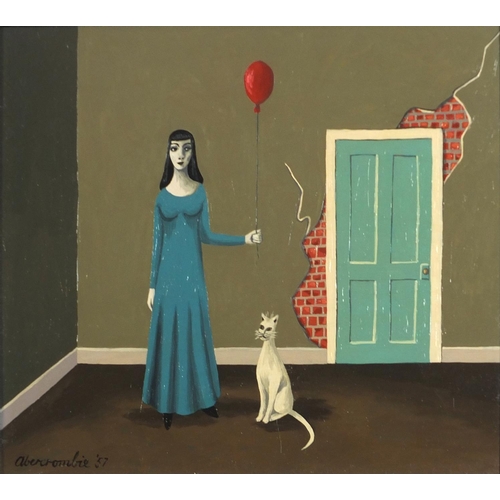

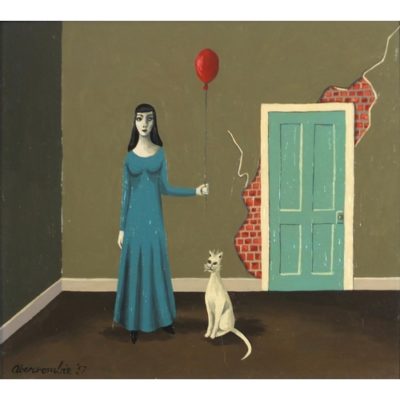

Abercrombie’s art features recurring symbols: shells, eggs, doors, moonlit flat landscapes, bare trees, owls, and over and over rooms nearly airless. She stares out of her paintings, a beaky-nosed gaunt figure not unlike a witch. Gertrude dabbled in the occult and psychic phenomena (especially hypnosis) as she did in most things avant-garde, and often wore a conical velvet hat as “the good witch.” Brooms and cats recur, proper companions for “the jazz witch of Chicago,” and although Gertrude seldom swept, she did keep company with at least 13 cats over the decades, mostly Maine Coons.

Chicago encountered surrealism with a Man Ray show in 1929 and a Giorgio di Chirico exhibition the next year, both at the Arts Club of Chicago. Dali’s Persistence of Memory drew record crowds at the World’s Fair in 1933. Abercrombie acknowledged both di Chirico and Dali as influences, but put the most emphasis on Magritte: “When I saw his work, I said to myself, ‘There’s your daddy.’” She also befriended Chicago artist Dorothea Tanning, who married Max Ernst in 1946.

And at some point along there, she discovered the Dreamlands. She painted her dreams, including prophetic dreams: in one dream, a white whale beaches in New England, which apparently happened the next day. As she wrote in one of her memoirs: “Miss A. tells about a dream. Upon waking she sees the room and everything in it exactly as it was in the dreams. ‘It was like walking into reality.’” A 1930s “early Gertrude” Dreamhounds of Chicago game could easily resemble a regular Dreamhounds campaign: players take on the roles of Abercrombie and her surrealist circle: Tanning, Eldzier Cortor, Karl Priebe, Julio de Diego, and Julia Thecla (who often dressed as a bird). Playing young Katherine Dunham seems irresistible here, using her knowledge of Voudun to map and guard the dreamers’ paths. Ivan Albright is the Cocteau or Dali of this scene, the irascible genius who refuses to go along with the others, spending years on massive works and only yielding to automatism when Hollywood calls.

But it might be more intriguing to run a “late Gertrude” game set in the 1950s or even the early Fall of DELTA GREEN era, as she (re?)discovers the Dreamlands and attempts to switch individual rooms and buildings from Thalarion into Chicago and vice versa. Images and icons pass between realms escorted by her army of cats, bouncing off “my moon,” as Gertrude called it despite NASA’s claims to the contrary. Her repeated windows, pictures of rooms inside themselves, doors, and lost buildings become a literally hypergeometric ritual, endless rectangular prismation building an artistic hypertrapezohedron.

Perhaps she briefly saw Thalarion in 1936 and then her first marriage in 1940 (or WWII, or a 1931-41 counter-ritual by Ivan Albright in the shape of his masterpiece The Door) froze her out of the Dreamlands until she found a new way in. The staccato bop of the horns and crotala of jazz overlaid the Zannisch chords of her boarder in 1955-56, Ernest Krenek, writing his opera The Bell Tower based on Melville’s story of a fantastic construction.

Does DELTA GREEN note the resonances between Gertrude’s openings of the way to Thalarion and the Situationists’ New Babylon project, begun in 1958 to rewrite Paris as Carcosa? Does a worried Margaret Brundage write to Clark Ashton Smith or August Derleth about the shifting realities she once illustrated for Weird Tales peeking through windows in her hometown? Does Ivan Albright once more try to close the door to Dream for Gertrude, spending 1957-63 on his painting The Window (with the intriguingly Lovecraftian title Poor Room—There Is No Time, No End, No Today, No Yesterday, No Tomorrow, Only the Forever, and Forever, and Forever without End)?

Through curator Katherine Kuh, Gertrude has access to the occult-minded modernist designer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and to the master of geometric prison shapes Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – do they reshape Harold Noecker’s first visions, or the crystal tower Mies designed for “an imaginary location” in 1920 Berlin? Is it significant that Gertrude’s last solo show in 1964 featured her painting The Magician and happened on Oak Street at the … Gilman Gallery?

Trail of Cthulhu is an award-winning 1930s horror roleplaying game by Kenneth Hite, produced under license from Chaosium. Whether you’re playing in two-fisted Pulp mode or sanity-shredding Purist mode, its GUMSHOE system enables taut, thrilling investigative adventures where the challenge is in interpreting clues, not finding them. Purchase Trail of Cthulhu, and its many supplements and adventures, in print and PDF at the Pelgrane Shop.