Ballad Hunters, News

Ballad Hunters Design Diary: The Regency Setting

by Tristan Zimmerman

by Tristan Zimmerman

Pelgrane’s forthcoming RPG Ballad Hunters — described in this Page XX article — is set in 1813 England and Scotland. This is the Regency era of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, of the Napoleonic wars, and of the Luddite revolts. It’s called the Regency because the reigning monarch, George III, is incapacitated by madness. His son reigns in his stead as prince regent.

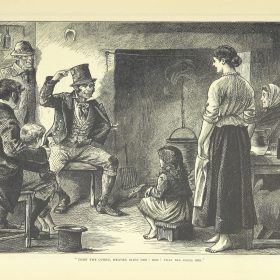

But Ballad Hunters is a game about ordinary people: their struggles, their joys, and their music. For such people, times are hard. Farmers are being thrown off their land. Slums swell with the unemployed. The sons of Britain are marching off to fight an unpopular foreign war, enlisting because they have no better choices. This is a more hardscrabble version of the era than is often portrayed.

‘Thou art none of my brother, Lazarus

That lies begging at my wall

No meat nor drink will I give thee

But with hunger starve you shall’

– Dives and Lazarus, Child Ballad 56

I’m not generally a Regency setting fanboy, so why choose it? Folklore as a field of study was beginning in earnest in the first half of the 1800s, and I wanted to put the investigators in that milieu. Of that half-century of British history, a non-British audience is most familiar with the Regency era, with its fancy balls and big Napoleonic battles. I’m a big believer in meeting the audience where they’re at. Don’t try to get someone excited about something they have no emotional connection to, but take something they’re already excited about and work with it. So I used high society and Napoleonic struggles as a starting point from which the audience can wade into an unfamiliar game concept.

RPGs as an art form shine brightest when they are about conflicts between individual people. That was the history I wanted to highlight. So I read up on the Luddites, the war’s effects at home, religion, social standings, and anything where I might find a conflict between two people, at least one of whom might plausibly know a folk ballad.

‘I dreamed a dream, Johnstone,’ she said

‘I doubt it bodes some good

I dreamed the ravens ate your flesh

And the lions drank your blood’

– Young Johnstone, Child Ballad 88

Writing a game about the music, struggles, and passions of ordinary working people meant engaging with the long shadow of Jane Austen. Outside of occasional revisionist works like Longbourne, most fiction set in Regency Britain follows Austen’s model and focuses on the rich. Workers make occasional appearances to curtsey and serve meals. But that was, of course, not the experience of most Britons of the era. They farmed other people’s land paying exorbitant rents, worked in the new textile mills, dug coal outside Newcastle, and starved in the slums. That’s where the action is.

The single most interesting detail I turned up in my research was that Britain’s wars with France from 1793 to 1815 were broadly unpopular every year except maybe 1803. Sure, people got excited about big victories like Trafalgar, but for the most part they opposed British involvement in these foreign wars. That doesn’t come across in Jane Austen novels because Austen belonged to the one group of British civilians credibly threatened by the French Revolution. Had the Revolution come to Hampshire, Austen and her wealthy relatives might well have been guillotined. The era’s widespread and popular criticisms of the war thus didn’t make it into her novels much. Anti-war sentiment is thus not something a modern audience expects to see in Regency fiction. But it’s a terrific focus for interpersonal conflict, so it’s something I made sure to have come up repeatedly in Ballad Hunters.

But when he came to fair Berwick

A grieved man was he

When that he saw his two bonny sons

Both hanging on the tree

– The Clerk’s Two Sons of Owensford, Child Ballad 72

Finally, one of the nice things about Regency Britain is that it fits well into most English speakers’ conceptions of what the past looked like. Even better, it’s close enough to the present that many of our modern assumptions still hold true. If you go with your gut, you probably won’t be too far off. In my experience, getting really passionate about the details of a historical setting can actually distract from the fun at the table, because players feel like maybe they can’t play this game unless they hold a PhD in the setting. In practice, that’s never true, but it’s even less true in Ballad Hunters.

Nonetheless, the book includes a fine chapter on Regency-era England and Scotland, focusing in particular on the lands along the Anglo-Scottish border. Many of the ballads are set there, and that makes the region particularly ripe for gameplay.

We anticipate Ballad Hunters going to crowdfunding in March 2026. The game’s already playtested and written, and is currently in layout. If you want to make sure you don’t miss it, you can sign up for my mailing list here.