Mutant City Blues, See Page XX

See P. XX: Mutant City Buddy Cops

See P. XX

A column about roleplaying

by Robin D. Laws

Mutant City Blues focuses on a standard-sized player group of 3 to 6 people. This lends itself to the ensemble style play of a serialized procedural show like NCIS, CSI, or Law and Order: Special Victims Unit.

If your player group consists of two people, consider drawing instead on the tropes of the buddy cop genre. We see this both in movies and on TV. Cinematic examples include Se7en, Lethal Weapon and The Heat. Television shows often pair a cop with a civilian, as seen in Castle and such genre mash-ups as Grimm, Sleepy Hollow or the short-lived Almost Human.

To replicate this last approach in Mutant City Blues you might consider teaming a genetically normal human cop with a mutant civilian. This could run as a prequel series, in which the mutant is the first ever to work with the police at all, in the very earliest days after the Sudden Mutation Event. This original teaming becomes the template on which the Heightened Crimes Investigation Unit of the baseline setting eventually bases itself.

Most player duos will prefer to each play investigators with super-powers. In this framework they’re partners in an HCIU unit, putting down their own mutant-related cases. An ensemble of GMCs might fill out the squad room as background players, described by you as needed.

The hallowed cliches of buddy cop storytelling call for contrasting personalities, typically a by-the-book voice of reason character and a maverick who believes in justice but can’t be tied down by red tape and procedure, dammit. A less extreme contrast puts a book smart trainee in the same squad car as a street smart veteran. The comic take on the buddy cop adds an overlay of The Odd Couple, teaming a fastidious officer with a slovenly one. You see this in both The Heat and the Andy Samberg comedy Brooklyn Nine-Nine.

Roleplayers generally prefer irresponsible characters to straight-laced types. (Unless they seek veto power over everyone else’s choices, in which case they’re off playing paladins in an F20 game.) Your player duo may have to rock-paper-scissors it to decide which has to fill the classic straight role.

Or you could find other oppositions unique to the setting. Strong mutant versus psychic mutant. Self-hating mutant versus proud genetic rights activist. Gorgeous cop with no visible genetic alterations versus the creepy one with bug-like powers.

For the classic by-the-book versus maverick pairing, investigative abilities can be distributed like so:

Voice of Reason

Anthropology

Archaeology

Architecture

Art History

Forensic Accounting

History

Natural History

Textual Analysis

Occult Studies

Bureaucracy

Negotiation

Reassurance

Chemistry

Cryptography

Data Retrieval

Document Analysis

Forensic Entomology

Forensic Anthropology

Maverick

Forensic Psychology

Law

Research

Trivia

Bullshit Detector

Cop Talk

Flattery

Flirting

Impersonate

Interrogation

Intimidation

Streetwise

Ballistics

Electronic Surveillance

Evidence Collection

Explosive Devices

Fingerprinting

Photography

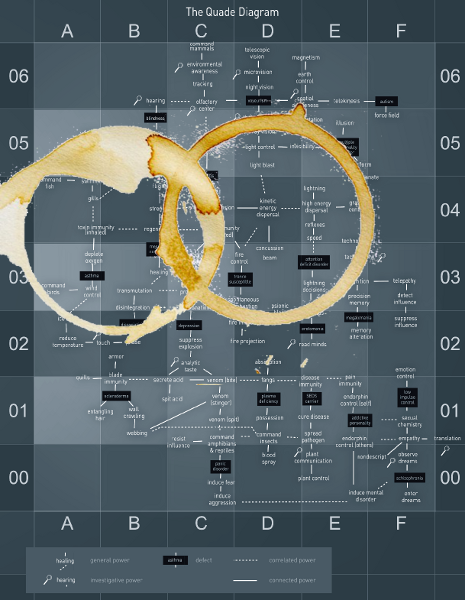

When choosing mutant powers, suggest that players buy the ones that include thematically appropriate defects.

Maverick: Addictive Personality, Attention Deficit Disorder, Depression, Low Impulse Control.

Voice of Reason: Asthma, Autism, Messiah Complex, Panic Disorder, Trance Susceptible.

In a buddy cop movie the two characters function as thesis and antithesis. As they investigate the case and confront its obstacles the two learn that each works better after accepting the virtues of the other.

(In this way both of the rebooted Star Trek films function structurally as buddy cop movies. In the first film, the maverick who gets things done by ignoring the rules (Kirk) discovers that he works best when he accepts the buttoned-down Spock. In the second film, they reset the pattern and repeat it all over again—except that Spock scores the win by going maverick and pounding the crap out of the bad guy.)

When building choices into buddy cop cases, look for procedural or moral dilemmas that highlight their fundamental contrast. Keep the tension in check: you want to spark entertaining badinage, not an outright rift.

Do they use a psychic power without a warrant?

Do they look the other way when a GMC squad member screws up a case due to his accelerating mutant defect? Or do they break the unspoken cop code and alert the lieutenant?

When a barhead accuses the maverick of getting rough with him in the interview room, does the voice of reason take the charge seriously, or back his partner?

Does the by-the-book cop let the maverick follow his hunch about dirty doings at the Quade Institute? Or does he insist on more evidence before charging into a situation pregnant with political blowback?

Use these questions as springboards when creating cases. Ask yourself what case could tempt them to use a restricted ability without a warrant, or navigate turbulent political waters. Construct the mystery around a key moment bringing the question to a head.

While improvising moments in play, use GMC reactions to spur exchanges over the cops’ contrasting styles. A sleazy mutant pimp informant tries to creep out the fresh-faced rookie. A society matron witness sniffs in disgust at the odor emanating from the crusty veteran’s unwashed trenchcoat.

Make room for moments that test the buddy cops’ loyalty to one another, where the best play requires them to work in tandem. These might occur directly in the cases themselves, or as ongoing subplots fleshing out the cops’ lives. An Internal Affairs officer comes sniffing around for dirt on the maverick. The button-down character’s wealthy father offers to pull strings for the maverick and clear his spotty record, if she agrees to convince his son to take a nice, safe desk job.

No buddy cop series is complete without plenty of banter in the squad car, whether stuck on a long stakeout, or during a wild chase sequence with the maverick maniacally at the wheel. If the leads aren’t arguing over who’s driving whenever they approach the vehicle, nudge them until they truly embrace the buddy cop spirit.