News, Yellow King Roleplaying Game

9 Tips for Remote Tabletop RPG Play

In the present COVID-19 crisis, many of us, myself included, have canceled our in-person roleplaying sessions to comply with social distancing or shelter-in-place public health regimes across the world.

This Thursday, after a hiatus, I’ll be switching my in-person game to remote. (I’ve just started “Canadian Shield”, an extremely variant Fall of Delta Green series.)

As more tips and tricks for remote play come up I’ll share them with you here on the Pelgrane site. Let’s get started, though, with what I’ve learned during previous forays into online tabletop.

1. Use the platform you already know.

Everyone who has already racked up extensive remote play experience expresses a preference for a particular combo of tools for video conferencing and the virtual play space.

For video, Discord, Zoom, Google Hangouts and to a lesser extent Skype all have their adherents. Each brings its own set of pluses and minuses. In the end your choice of video app may depend on the quirks of each player’s device setup. You may wind up shuffling through a bunch of them before you find the one that happens to function for your entire group.

As far as play spaces go, Roll20 already has resources for 13th Age and GUMSHOE. We’ve just added DramaSystem.

If you’re already familiar with a video conferencing app and/or virtual tabletop, skip the learning curve and use that. It works; don’t fix it.

2. If you haven’t done this before, I prefer Google Hangouts and Slack.

Google Hangouts hasn’t let me down yet. It’s free, and pretty seamlessly handles switching to the person currently speaking. That’s the most important feature of a video app for game play and it does it well. Google has announced that they’re ending this service soon, but if I understand their PR correctly, what they’re actually doing is rebranding their video chat to sound more business-friendly. Google can hook you on a service and then whip it out from under you like a rug, but I’m guessing that we’re safe when this one changes to its new incarnation. I wouldn’t bet on that happening according to its original timetable, either.

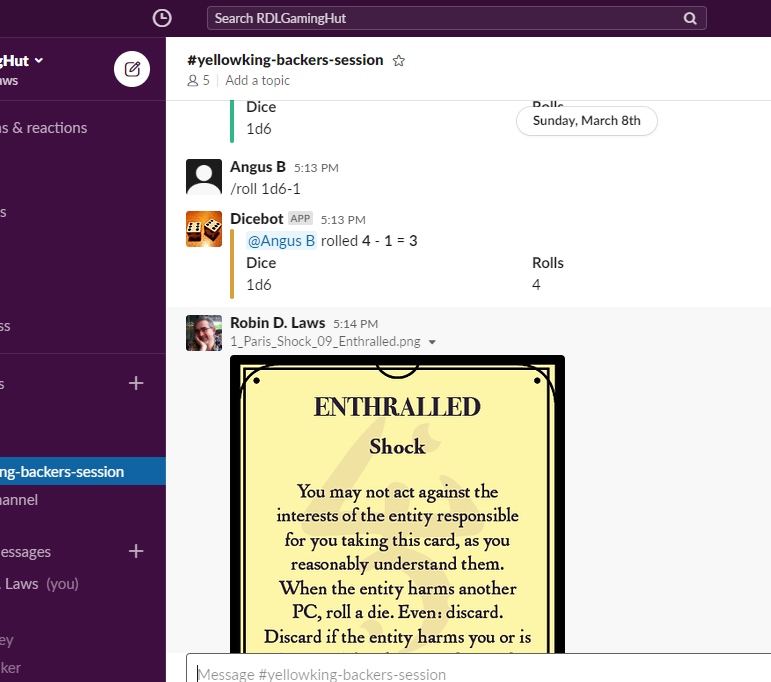

For GUMSHOE and DramaSystem, I use as my virtual tabletop a tool not remotely designed for that, the group project messaging platform, Slack. It is a platform I use for other purposes every day and know how to use. I already use it for face-to-face when running The Yellow King Roleplaying Game, having found it the best solution for serving electronic Shock and Injury Cards. When teaching that system I upload a card image to the game’s main channel so everyone can feel its horror. I also drop the cards to each player, in our private message inbox. When they discard cards, I delete them from the private message inbox, so that it contains only the cards currently held.

Maps, images, and other handouts I upload to the main channel as well.

Slack’s advantage over its competitors in its category lies in its ease of use. A newbie can immediately figure out its simple and intuitive interface.

I’d use Slack for any game that relies primarily on dialogue and description, which describes both GUMSHOE and DramaSystem.

In fact I’d probably use it to run 13th Age. I don’t use a battlemap when running that in person, so wouldn’t bother with one in remote play either.

A game that does require a tactical map will naturally push you toward one of the purpose built virtual tabletops. These all have to handle D&D and Pathfinder. If you’re playing a game of that crunchiness online you’ve bought into the extra handling cost.

3. Leave in the Socializing.

Especially now, much of the point of an online game is to feel the connectedness we might ordinarily seek out around a table, at a con, or in a game cafe. The formality of the online experience might tempt you to cut right away to the case. You may know each other less well, or not at all, if playing online. Even so, give everybody time to chat a bit before getting started.

4. Expect a shorter session.

Though this varies for every group, in general the online meeting format promotes an efficiency you may find yourself envying when you return to face-to-face. Video conferencing requires participants to be conscious of who has the floor at any given moment. It reduces crosstalk and kibitzing. People used to conducting real meetings on video tend to step up to help guide the discussion and move toward problem-solving. The software does a good bit of your traffic management as GM for you.

For this reason you’ll find that remote play eats up story faster than a leisurely in-person session. The pace of any given episode more closely resembles the tighter concentration typical of a con game group that has found its rhythm. Your group will likely decide what to do faster, and then go and do it with fewer side tangents, than they would at your regular home table.

When this happens, you may find yourself wondering if you shouldn’t add more plot to keep your ending further away from your beginning. Instead, embrace this as the dynamic operating as it should. If it takes you three hours to hit five or six solid scenes, where in person it would take four, that’s a good thing.

5. Expect a more taxing session.

In addition to respecting the pace your session wants to have, you should aim for shorter sessions because the experience of gaming remotely takes more out of you, and each of your players, than face-to-face will.

Many of you will be sitting in less comfortable chairs than you’re used to being in. Those with home offices may already have been in those chairs for an entire work day already.

The concentration required to pay attention to people on video conferencing taxes the brain more than face-to-face. You’re trying to assimilate the same amount of communication from one another with fewer cues to work with. This tires any group, physically and mentally. Expect that and pace your game accordingly.

When you see a time-consuming setpiece sequence coming up, check the clock to see if you’ll be able to do it full justice given these constraints. Never be reluctant to knock off early and leave folks wanting more next time you all join up.

6: For Slack, use the Dicebot app.

To return to a platform-specific point, the Dicebot Slack app allows any participant to roll dice right in the channel. It easily does the d6 plus spend modifier for GUMSHOE. It inherently reminds players to announce their pool point spends before rolling, another neat advantage over physical dice.

Speaking of games that scorn the battlemap, Dicebot also handles the more complicated positive d6 + negative d6 + modifier roll seen in Feng Shui.

7. Whatever the platform, use a dice app if you players can possibly be coaxed into it.

Some players need that tactile dice-touching fix. I wouldn’t force online rolling on them, but having rolls take place visually in front of everyone does enhance their emotional impact by allowing everyone to see and react to the results.

Dice provide suspense . A die roller, in whatever platform, shares that edge of the seat moment when you see who succeeds and who’s about to take a Shock card.

8. Use a shared Google Doc for note-taking.

Since they’re all on a device anyhow, encourage your players to contribute to the group chronicle by setting up a shared Google Doc. Gussy it up with a graphic touch or two to build tone and theme.

9. Keep online versions of character sheets.

You’d think players won’t lose paper character sheets if they’re not leaving the house, but of course we misplace stuff in our own places all the time.

For GUMSHOE, the highly recommended Black Book app does all of the work of keeping online character sheets for you. It has just extended its trial period for player accounts.

Absent a specific tool, keep updated character sheets in a Dropbox folder or, for games where characters are simple as they are in DramaSystem, in a Google Sheet. I’ve done this for my “Canadian Shield” game.

Stay tuned for more tips. I look forward to the day when I can update this post to remove references to the pandemic as a current event. Until then, stay safe and, as much as you possibly can, the hell inside.