News, Yellow King Roleplaying Game

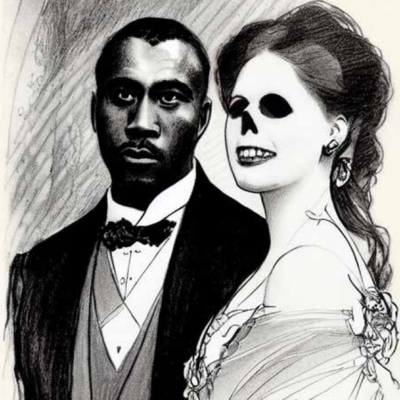

Legions of Carcosa AI art

by Robin D. Laws

by Robin D. Laws

Legions of Carcosa, the foe and creature book for The Yellow King Roleplaying Game, constitutes an experiment in Pelgrane’s use of AI-generated art in its products. An experiment that drips mystically corrupt paint, gallops like a typewriter-headed hyena, and buzzes like the insects of the Hyades.

I have been exploring the capabilities of AI art for about a year, starting when the various platforms started returning kinda sorta nearly publishable results. You may have seen some of these early hazy, gloopy pieces illustrating blog posts. Now, in early 2023, AI platforms can return stunning, surprising, and horrifically delightful images.

Over this time I have come to see them as an additional way to express the ideas that enrich your tabletop gaming stories.

Using AI art certainly requires thought and care on both the creative and ethical fronts.

Currently, platforms like Stable Diffusion, which I used to make the images for Legions of Carcosa, produce attractive work within a certain narrow band. In its wheelhouse are landscapes, locations, technological devices, and close-ups of people framed so that their hands don’t show. It used to be bad at getting two eyes pointed in the right direction but suddenly isn’t. In addition to hands, AI currently struggles with dynamic full body poses, large numbers of people, or subjects that don’t have bits of them protruding awkwardly out of the frame. It’s best at making things that already exist[1]. It can occasionally design a cool new previously non-existent creature, device, or place, but can’t then replicate that design in a second pose or from a different angle.

However, I have found, and hope you will agree, that the narrow band it perfectly suits is a horror game about reality shifting, art history, and warped timelines. One that pits the heroes against the King in Yellow and other creatures freshly escaped from the uncanny valley.

Stable Diffusion allowed me to create creature images that evoked the four historical periods, two of them imaginary, the game takes place in. By carefully selecting the text input prompts, and reference images for Image to Image generation, I was able to place the foes from the 1895 Belle Époque Paris settings in the art style of that era.

For the other three settings, I was able to control color palette, historical reference, and period styles to create distinct looks that convey their contrasting moods, themes, and visual motifs. The images look quite different from each other but within each of the four settings conforms to an overall production design.

The ethical care comes in when you consider that the tools can be used to create images that infringe on in-copyright works, and images that clearly do not.

For example, the work of Vincent van Gogh is now clearly in the public domain. Artists have been pastiching his style ever since it achieved iconic status. You can ask Stable Diffusion to make you a new van Gogh, and it will. As with other artists whose faces are as famous as their work, it takes some adjustment to the prompts to get a picture by van Gogh but not of van Gogh. Eventually though you can get it to make a van Gogh portrait of Marie Curie.

The tool also allows you to take an image you own the rights to, for example a photograph you took yourself, combine it with your freshly minted van Gogh, and create a new image based on both.

Also clearly not infringing.

However, you can absolutely use the tools to generate a picture that barely alters an existing in-copyright image, in what I would argue clearly violates that copyright[2]. You can also use it to create images that do not copy any one existing image from a current or otherwise in-copyright artist, but nonetheless patently swipes their singular overall look. Under some interpretations of IP law, which generally holds that you can copyright the specific expression of an idea but not the idea itself, that might be legal. To my mind it isn’t ethical[3].

In keeping with this principle, when creating the images for the more recent time periods covered in Legions of Carcosa, I discarded the occasional image that came out obviously resembling the work of a specific in-copyright artist.

Some take the position that every single picture the platforms make is legally and/or morally derivative. By using AI images at all, I’m clearly reaching a different conclusion. That requires an argument in favor of influence. This may cause eye glazing in normal humans, so please feel free to bail when it goes too far into the woods for you.

Intellectual property rights exist in a balance between copying and influence. The first is unacceptable, the second necessary to the practice of any art form. Any working creator has to constantly navigate the legal and aesthetic distinctions between those two concepts.

We absolutely have to study the works in the art forms we practice, very much including current works, to see how they are put together and how technique works. We then go off and create our own works, informed by those general principles. Maybe the first things we do come out embarrassingly close to the works that inspired us. In the end successful artists find a bridge between the familiar and the unique. When I tell aspiring writers to read, and read widely, including works outside their favorite fields, I am telling them to seek out influence. Ideally the writer comes out of that process of influence absorption with a unique style that may contain threads of, say, Jack Vance, Stephen King, and Don DeLillo, not just straight-up Stephen King. We wouldn’t have Star Wars if George Lucas hadn’t absorbed Flash Gordon serials, John Ford, and Akira Kurosawa, and then used them as ingredients for his own sensibility. Certain artists cast such a wide shadow over their fields that their influence is inescapable even in traditional illustration. Almost any monster anyone draws today has some Giger in it. We wouldn’t have any tabletop roleplaying game other than Dungeons & Dragons if early TSR had realized its legal hopes and earned a ruling that no one could draw influence from it to create a new work of their own. Your roleplaying game designs will suck if you haven’t studied works in the field and learned the lessons they can teach you.

Artists also draw influence from existing works, including but not exclusively masterworks long in the public domain. This process often starts with literal copying and then as with any other art form blossoms into a dialogue between prior work and unique individual style.

The AI platforms used the mass calculation powers of modern computing to absorb influence from more images than any one human artist could ever draw influence from. An end user who takes care not to ask for a direct rip-off of an in-copyright artist, and rejects any pieces that come back looking like one, makes use of only broad strokes elements of an image that no one owns. AI images are shockingly good at the way light falls on a figure or object. Learning to reproduce that is hard for traditional artists. But no one owns the physics of lighting. Or what a stone wall or a bird looks like[4]. Or a glistening surface. Or the visual concept of brutalism or a 2020s color palette, or a meticulous line or impasto brushstroke.

To recap then the rules I used for Legions of Carcosa AI images were:

- Images that clearly resemble the work of a public domain artist are acceptable.

- Images that clearly resemble the work of an in-copyright artist are not.

- Broad influence is as acceptable in this new platform as it would be in any other creative pursuit.

For future projects I might add other rules. No real people are depicted in Legions illustrations. In another book a line might need to be drawn between historical figures, who are acceptable to depict, versus people who retain rights to their images, and are not.

Legions features an original cover and AI images for all interior art. This creates a visual unity for this particular creature tome. This one choice does not mean that Pelgrane intends to go all AI. For most other books I’d personally prefer either all original art or a mix of commissioned pieces and AI. However I do see a bright future for Stable Diffusion in covering for artists who have to drop out of a project at the last minute.

Any treatment of intellectual property rights offers endless opportunities for rabbit holing. As you can see by the fact that this article contains @#$% footnotes. This goes triple for discussions of IP law. Fine legal distinctions we as creators need rarely appear clearly in any piece of legislation. Instead they’re made up piecemeal by judges in response to specific, usually weird, cases. And let’s not get into wildly disparate approaches to artist’s rights between jurisdictions, all of which Pelgrane sells into.

Ultimately, like bourbon, AI art platforms can be used responsibly or irresponsibly. I hope you will check out Legions of Carcosa and agree that it enhances and deepens your presentation of the shattered realities spawned by the pallid king. And that the few horribly clawed hands I chose to leave in were meant to be horribly clawed.

[1] Conceivably, the better it gets at making conventional images, the worse it will become at surreal horror weirdness.

[2] I almost said “as almost anyone would argue” before remembering the work of Richard Prince, who has had his slightly altered versions of other photographers’ images ruled as sufficiently transformative as to not violate copyright.

[3] Though even here you can point to gray areas by looking at traditional artists who owe an obvious debt to the styles of specific predecessors.

[4] Current platforms have figured out stone walls and are increasing their batting average on birds.