News, See Page XX

The Vroomfondel Technique

Player input into a game is a wonderful and multifaceted thing. It’s not just that it takes some of the burden of creativity off the GM (“I don’t know, you tell me who your character knows that’s an expert on Etruscan demonology”), it also gives the players a sense of investment and ownership, and gives unexpected elements that the GM might never come up with on their own. The Yellow King roleplaying game, for example, makes player creativity a key part of setup, asking each player to describe a ‘Deuced Peculiar Thing’ that recently happened to their character. 13th Age, with its One Unique Things, is similarly enthusiastic about player input.

Player input into a game is a wonderful and multifaceted thing. It’s not just that it takes some of the burden of creativity off the GM (“I don’t know, you tell me who your character knows that’s an expert on Etruscan demonology”), it also gives the players a sense of investment and ownership, and gives unexpected elements that the GM might never come up with on their own. The Yellow King roleplaying game, for example, makes player creativity a key part of setup, asking each player to describe a ‘Deuced Peculiar Thing’ that recently happened to their character. 13th Age, with its One Unique Things, is similarly enthusiastic about player input.

However, as any night of improv comedy can demonstrate, there are problems with suddenly calling for input. Some people – even some roleplayers – freeze when put unexpectedly on the spot. Others get zany, coming up with suggestions that are weird, ill-fitting or designed to evoke a laugh or one-up the last idea. That’s fine in some circumstances, but can be tricky when the GM’s trying to weave all those player inputs into some sort of coherent existing narrative.

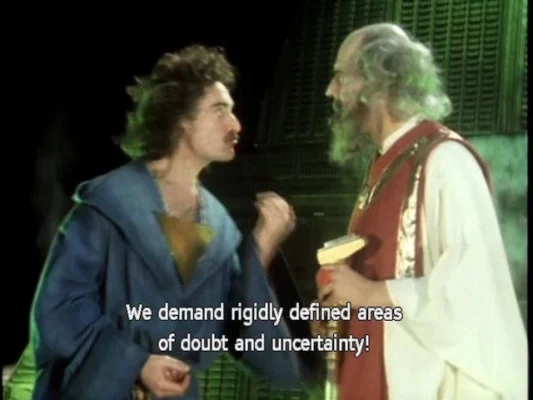

The trick is in phrasing the question posed to the player, so you leave room for all those juicy, surprising responses while guiding them to the right narrative ballpark. Giving them, as the quote suggests, rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty.

Some approaches:

- Prompt where you want creativity: The GM provides the raw facts, the player adds details to those facts. “Your uncle was found dead in the hotel room – what was strange about the body?” “You were trained in a monastery – what secret do the monks there keep hidden?”

- Give the end point, let the player determine the route: A variation of the above – say where you want the player’s answer to end up, but let them decide how to get there? “Recently, you’ve become fascinated by the occult – why?” “What convinced you that you were abducted by aliens?” “What convinced you that you were the chosen hero who’ll save the world?”

- Encourage riffing and yes-anding: If you’ve got multiple players giving inputs, take the output of one player and feed it into the next. If Alice’s come up with a haunted train station, then ask Bob a question that connects to it while still leaving Bob plenty of free space for creativity. “You have a recurring dream about being on a strange train – where does it take you?” “One of your relatives perished in an oddly train-related way – what was it?”

- Define limits with guided questions: Sometimes, you’ll need to keep players away from a particular concept – say, vampires – without actually mentioning that concept, because you want the existence of, say, vampires to be a surprise later in the campaign. In this case, ward players away from the forbidden zone by signalling that their answers can’t be conclusive – but ensure you can later pick up their answers and tie them to, say, vampires. “Your old college mentor vanished without a trace, and you never found out what happened to him? What one cryptic clue did he leave behind?” “As a journalist in London, you get wind of all sorts of strange political scandals and stories? What’s the one bizarre, occult-tinged rumour that you’ve always wondered about but never managed to pin down?”