See Page XX

Tell Me Lies, Tell me Sweet Little Lies – Part 1

Tell Me Lies, Tell me Sweet Little Lies

Tell Me Lies, Tell me Sweet Little Lies

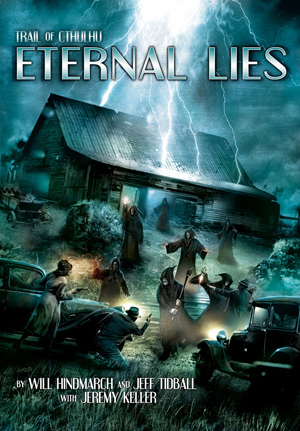

Converting Pelgrane’s ‘Eternal Lies’ Campaign to Call of Cthulhu

By Andrew Nicholson

Part One: Fools Rush In

It started as a way to persuade a group of gamers to try Trail of Cthulhu instead of their more usual fare.

“Hey”, I said, “…it turns out Pelgrane are looking for people to playtest a new campaign they’re hoping to publish – wouldn’t it be cool to see it first?”

There were nods and grunts around the table, accompanied by the supping of cola and devouring of curry … and thus it was decided.

I was more than ready for something a little different. I’ve been a keen Cthulhu Keeper ever since picking CoC up in about 1984, and after two years of only getting to run the occasional scenario, I was seriously looking forward to running a dark horror campaign.

A short while later (and a name drop or two) I had in my hands the playtest documents for Act One of Eternal Lies… and that was it, I was hooked.

Fast forward a few years, and Pelgrane announced the campaign was ready for publishing. People all over the internet were asking about it, and playtesters were enthusing about what a great campaign it was… but there was one repeated question:

“Does it have Call of Cthulhu statistics? If not, will there be a Call of Cthulhu conversion?”

Pelgrane’s Trail of Cthulhu range is, without doubt, excellent. The GUMSHOE system has many fans. However, much like many family relationships, there are those who will always prefer its older and better known brother. Some do not like GUMSHOE’s spend system. Others are fond of ToC – but just plain love CoC.

Having enjoyed the first act of the campaign so much, I felt it was a huge shame people might miss out on it. So, looking at the playtest notes for the first act, I did a rough conversion on scrap paper and thought: “I can do this – I know both systems pretty well, I’ve got the experience, and it shouldn’t take long either”

A couple of conversations with Simon at Pelgrane later, and we had it agreed. I would write a conversion of the campaign, and we hoped to have it ready in time for release at the same time as the book.

And then the files of the campaign arrived. I devoured them greedily, and it slowly began to sink in. Act One was only the introductory act. Act Two was big. Very Big. I also realised the way I had originally intended to write the conversion notes just wouldn’t do; it would have been fine for those with a passing familiarity with GUMSHOE, but would not give enough support to those who had never played it.

Also, we only had a few months to do it. My conversions would not only need working out and writing, but some playtesting to make sure they weren’t completely unreasonable.

In a word: Eeek.

But there was no way I was not going to do this. I had given my word, after all – plus, was I going to let an opportunity to do something cool for the Pelgrane slip away? Hell, no.

The First Decision : Keeping the Flavour

I read through the system conversion ideas in the back of the Trail of Cthulhu rulebook.

I sat down with a cup of tea, and gave it some thought.

I decided that Rule number 1 was: Preserve the flavour of the campaign’s encounters where at all possible.

By this I mean that players using either system would get as close to an identical experience playing the narrative of the campaign as could be managed. Tough encounters should remain tough. Easy encounters should remain easy. Some encounters should require sacrifice of irreplaceable resources. Investigative encounters should require the players to think, but not necessarily be dependent on random dice rolls.

Trail of Cthulhu approaches investigations slightly differently from Call of Cthulhu. In particular, there were couple of distinct tenets that I wanted to preserve: “Make the game player focussed”, and “It’s not rolling dice to find core clues that is important – it’s what investigators do with them”.

Player Focussed

Player focussed games aim involve the players as much as possible whenever anything happens. The vast majority of the dice rolls are made by the players, and even in situations where they are opposed by NPCs the Keeper rarely rolls a die.

The theory is this keeps the players feeling involved and also means that if something happens they feel they had some input into it. There are few things worse for a player than to feel that something nasty happens “automatically” to them without them getting to at least roll dice. It may be a mainly psychological reaction, but it’s one I’ve seen time and time again.

So, to preserve this, I approached most situations in the conversion in the same way. When potential conflicts arise like an investigator hiding from an NPC, rather than call for opposed rolls (something that Call of Cthulhu doesn’t have the best system for anyway), I would put the onus on the player rolling against their skill, with a negative modifier to account for the skill of their opponent. This was a quick and easy conversion to do, still fits the Call of Cthulhu system – and I could still list the NPCs skills for those Keepers who wanted to go with the opposed roll approach.

The exception was in combat. While it was easy to make non-combat situations player focussed, combat would require far too many spot rules, and would not feel like Call of Cthulhu. Combat, therefore, shouldn’t be messed too much with.

Core Clues

Trail of Cthulhu also uses the concept of core clues – clues that are so vital to the investigation that without them the investigation will stall. Its been a long accepted flaw that in some Call of Cthulhu scenarios, one failed roll can mean the entire adventure stalls to a halt unless the Keeper arranges for some sort of work around.

One of the things I like about Trail of Cthulhu scenarios it clearly identifies these clues, and Eternal Lies is no exception. However, the question becomes – how do we approach this in Call of Cthulhu?

I looked at the suggestions in the main Trail of Cthulhu rulebook. They seemed serviceable… but I thought I could do better.

I had been using a house rule in my Call of Cthulhu games for several years, derived from Trail’s core clue concept. It had been playtested on numerous occasions, and seemed pretty effective. An investigator still has to roll against a skill to find a clue, but failure on the dice doesn’t mean failure to find the clue; it means that extracting or deciphering the clue becomes more difficult – the exact problem being decided by the Keeper based on the circumstances. I find this works very well, and keeps the acquisition of clues interesting for the players while still keeping the investigation on track.

However, while I knew this would be an approach many Keepers would be happy with, I also needed to account for those who are less comfortable with improvising, or prefer either more rules orientated approach. So, we playtested some alternatives solutions, and a couple of them (along with the rulebook’s suggested approach) are discussed in the conversion.

Having dealt with the more general rules issues, now I needed to start looking at specifics…

(end of part one – part 2 will follow next month!)