News, See Page XX

See Page XX: The EZ One-Shot System

A column about roleplaying

By Robin D. Laws

Sometimes you want to run an entirely casual tabletop session that requires next to no prep on your part, and zero learning curve for the players. For example, you might want to run a game around a dinner party, maybe with a break in the middle for food. Or the trad game you hoped to run has been scuttled by a last-minute absence, let’s say of the player of a character crucial to last week’s cliffhanger. You might want a dead simple thing to run this for tabletop-curious friends as a soft introduction to the form.

Here’s a rules framework I recently put together that fits those needs. The play that emerges from EZ One-Shot can run toward interaction or a highly abstracted version of procedural problem solving. With the tactical element stripped away, character interaction takes the spotlight. EZ One-Shot leans heavily to the story side of the rpg spectrum, with players taking an authorial role beyond the control of their characters’ behavior and dialogue.

Character Creation

The players build characters with a handful of questions you pose to each player in turn.

The GM creates these questions ahead of play. In addition to thinking of a setting and premise, and perhaps jotting down rough notes to enable you to describe them later to the players, this is the only preparation required.

In addition to questions that establish the basics of character concept, pose one question that establishes each cast member’s broad area of procedural competence. Reword the question “what is your role on the team?” to fit your chosen genre. Depending on what that is, selected, players will answer with the equivalent of character classes, occupations, superpower themes, or templates found in trad games:

Fighter, ranger, thief, druid, paladin.

Dilettante, bookseller, professor, occultist, detective.

Super strength, genius, fire powers, shapeshifter, magician.

You know the drill.

Break your question set into two parts. The first asks the player to establish their character without knowledge of the others. The second round of questions creates the dynamic that exists between the members of the group as the action begins.

A sample set of questions for a teens versus monsters one-shot might read like this:

First round

What is your name?

If you found yourself in trouble, what ability or quality would you rely on to get yourself out of it?

How do your fellow students at Anne Rice High regard you?

What personal limitation would you would most like to overcome?

Second round

Why do you belong to this group?

When you need help, you go first to the character whose player is sitting on your left. Why is that?

The person in the group you most worry about is played by the person to your right. Why is that?

Finally, plan the central problem the group will face in the story. Pick one that players will easily grasp.

- The mountain dragon has captured the prince regent.

- An alien creature in the woods hungers for prey.

- Baron Killshot has filled the science museum with deadly traps.

Starting Play

When play begins, quickly describe the setting, giving the players enough clues to indicate what genre they’ll be making characters for.

Beginning with the player to your left, or the player most able to jump in to get things rolling, pose the first round of questions. Go around the table clockwise until everyone has answered the first round. Then go around again to pose the second round, until everyone has answered.

Give each player three tokens, explaining the resolution system described below.

Then begin the story. Get the best results by with a scene where everyone has already gathered together, and then discovers the central problem posed by the narrative.

Resolution

When characters attempt challenging actions where suspense attaches to the outcome, and they are not directly acting against other player characters:

- Determine whether the character is performing an action within their specialty. Unless some extraordinary counteracting circumstances pertain to the situation, the character succeeds.

- Otherwise, invite players to spend one of their tokens to either increase or decrease the odds of success.

- The GM rolls a d6.

- The die result is modified by number of tokens spent. Each token spent for success decreases the die result by 1. Each spend for failure increases it by 1.

- If the action was within the character’s specialty, decrease the result by 1. For this to come up at all, the attempt must have faced extraordinary opposition.

- A result of 3 or less succeeds.

- When a failure would impede the forward action of the story, a success occurs, but at a cost to the character performing the action.

Characters need not be present or involved for players to spend tokens. This choice happens on the authorial level.

GM may rule certain goals impossible period, or impossible without groundwork successes that make them credible.

Token Distribution

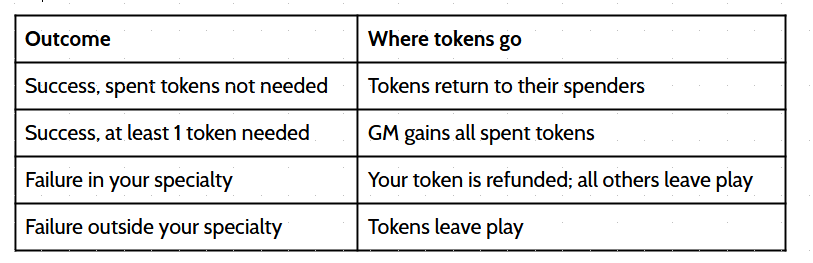

Whenever players spend tokens on an action, determine where the spent tokens go.

The GM starts with 0 tokens but can gain them during play. When they have tokens GMs can spend for or against any action.

If the unmodified result would have brought success absent the tokens, and no one spent for failure, players get their tokens back.

If the player succeeded only because tokens were spent, the GM gets the tokens. Including any spent in opposition.

When a player spends and fails on an action within their specialty, they get their token back, but all tokens spent by others leave play.

Player vs. Player Resolution

When one or more player character acts against one or more others, the players and GM vote on the outcome by choosing to spend a single token, or sitting out. If an equal number of tokens are spent on each side, the GM designates one side odd and the other side even, then rolling a die to see which one wins.

And those are all the rules. In the next installment of this column, I’ll provide a sample scenario and comments on how it went during play.