See Page XX

See Page XX: The History of No

A column about roleplaying

by Robin D. Laws

Previously on See Page XX, I talked about the difficulties we occasionally hear about when GMs who have trained themselves to say “no” come to the GUMSHOE  system with those assumptions in mind.

system with those assumptions in mind.

This time I’d like to look at how early roleplaying culture took on that mindset, and how assumptions are shifting during the current RPG renaissance.

GUMSHOE, along with many other games, actively works to move the story forward. When we spot a barrier to narrative development, we add tools to help GMs and players push them out of the way.

For example, the Drives system found in many GUMSHOE iterations, from Fear Itself to The Yellow King, puts the onus on players to engage with the premise and take actions that lead to an engaging story.

It works to correct a previous prevailing unspoken assumption, in which it is the GM’s job to entice reluctant players to take risks with their characters. Drives remind them to make active choices a perfectly rational but uninteresting character might go to some trouble to avoid.

This assumption, like so much else, arises from the early history of the form, which thought more about reward and punishment than about building a fun story together. Early players learned at their peril not to make “stupid” mistakes that would kill off their characters. Drives work to change the question from an older model, “how can I avoid deadly mistakes?” to “what inspires me to make exciting choices?”

To repeat a Thing I Always Say, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson weren’t trying to create a new narrative art form when they developed the ideas that turned into Dungeons & Dragons, the original roleplaying-game-as-we-know-it. They were working in the wargaming tradition, inventing a new game that reduced the unit size from a squad, battalion or legion to a single individual with a sword or pointy hat.

Included in that brainwave was the brilliant, habit-forming concept of the experience point, a currency you continue to accrue to your character over time. That persistence and growth led by inevitable consequence to narrative.

But it also created an adversarial dynamic between DM and players. The DM has an infinite supply of experience points, creating an environment that withholds them from players until they fight the world and pry them loose.

Early DM advice advised against excessively punitive treatment of the players and the characters, not because the game wasn’t a contest between the characters and the world, but because the game stopped working when DMs abused their unlimited power. DMs had to remind themselves that they weren’t there to crush the players, but to give them the most exciting set of challenges.

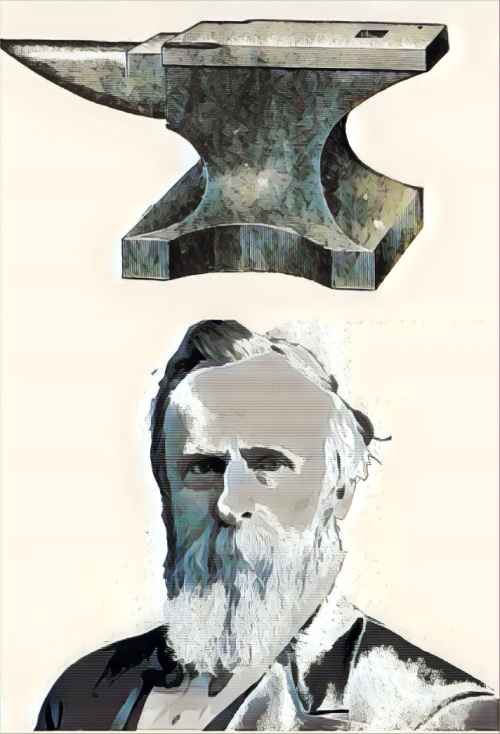

Power-mad Dungeon Masters weren’t a mere matter of folklore. When I interviewed him for 40 Years of Gen Con, Dave Arneson recalled the time when he sat down to play with a young DM, who promptly narrated a massive anvil plummeting from the heavens to squash his character to a pulp. “I killed Dave Arneson! I killed Dave Arneson!” the kid cried, to the delight of surrounding tables. Such were the terrible lessons of the early dungeon wars…

Along with warnings against this sort of stuff in early books came contrary messages. DMs were advised to punish uncooperative players with bolts of electrical damage to their characters, or presented with the infamous instant-kill traps in Tomb of Horrors.

We often think of adversarial roleplaying as something that the DM inflicts on players. Anyone whose original Gaming Hut really had shag carpeting, wood paneling and a Peter Frampton album for a screen no doubt remembers players coming at them hard. They rolled at you either in search of those addictive XP and the new levels they brought, or just the opportunity to screw with The Man, who happened to be you. The greater the emphasis on the reward, the more the DM had to ride herd, controlling cheating, minimaxing, and rules lawyering. This was not an era of “yes and” but of “duh, no!”

The experience point still rules the land of D&D, but these days in a more enlightened tyranny. Over the years XPs have become a pacing element measuring the rate at which your characters inevitably get better. Years of design adjustments have cut out exploitable jackpot effects. Later customs of play encourage the whole group to progress at the same rate, and for replacement characters to rejoin at par with the rest of the party. No longer do we assume that they restart at level 1 and try to stay alive long enough to catch up on the XP curve.

Other games carried over the assumptions of rapacious players you had to say no to. Build point games such as Champions and GURPS rewarded system mastery and the search for bargain-priced powers and disadvantages. They relied on GMs to watch for and curtail abuses.

Assumptions of power and control extended to authority over the narrative. The idea that a player could invent a useful prop to describe during a fight scene seems like a dead obvious collaborative element today. When it appeared in the original Feng Shui, it blew minds. Even so, the first edition of that game is nonetheless rife with passages assuming that the players want to hose you, the GM, and that you can turn that thirst to your benefit.

With decades of story-emulating play devices behind us, players have not only become less rapacious overall, but also less movable by either bribery and punishment.

GUMSHOE’s first version of Drives included a mechanical penalty for players who refused to go along when the GM invoked them. This proved unnecessary; once reminded of a Drive, no halfway cooperative player refuses the adjustment.

In a world where thirteen year olds exist, the hunger for advancement and putting one over on the GM will never vanish entirely. But their version of fun is no longer the baseline for every table. Our latest generation of new players is as much influenced by actual play podcasts and the hunger for character and story as by an unruly desire to minimax and grub for XPs.

As player behavior has changed in the aggregate, what the designer needs to do to facilitate maximum fun for all has altered as well. Design change has both shaped, and been shaped by, cultural shifts within the roleplaying community writ large.

Gaming culture can change invisibly as our personal assumptions remain fixed and unexamined. That’s why, I think, when a GM who has played many games over the years misreads a rule, that the misreading will default to the forbidding, even in a system built to be permissive.

That presents a communications challenge, it’s also a tribute to the complexity of a form that continues to evolve in dialogue with its audience of collaborators.